Experienced supply chain professionals understand the types of damage that may occur to a package and the root causes of this damage. Although some amount of stress may be unavoidable, proactive planning and testing can minimize the amount of damage that occurs to packages during transit.

The product’s journey

Understanding the specific journey of each product through a complicated supply chain allows planners to anticipate potential sources of damage. Proactively designing packaging that can withstand harsh transit conditions such as heat, humidity, drops, and turbulence helps minimize damaged packages and subsequent product returns.

.png?width=800&height=829&name=Group%2043%20(1).png)

Packaging influences brand perception

Each touchpoint consumers have with a brand influences their perception of that brand. For brick-and-mortar retail, consumers will first interact with the package that encases the product before touching the product itself. In e-commerce, consumers may also interact with the corrugated carton that is used to ship the product package directly to the consumer.

Brands have a vested interest in making sure that packages arrive to consumers intact and that the products contained in the package will work as intended. When a consumer receives an intact package, they are subtly assured that their product was protected during transit and assume the product is in good working order.

However, if a consumer receives a damaged package, they may have immediate concerns regarding whether the damage done to the package has also caused damage to the product, which may affect its function and performance.

Master outer cartons (MOCs) protect retail or primary packaging as they travel from the factory to the distribution center (DC). Designing MOCs to withstand the rigors of their journey to the DC helps ensure that both the carton and the product package that ship to the customer will be unblemished when they leave the DC. Additionally, designing retail packaging and MOCs in tandem is beneficial to gain the most efficiency.

Common transit conditions that lead to product damage

Transit testing is designed to simulate the shipment conditions for all of the packaging that surrounds the product. This includes the product package and the master outer carton (MOC). Product damage may occur as a result of transit, package handling, or damage that occurs during storage.

Transit damage

Products may get damaged while the product travels from one location to another location. This type of damage may include:

|

|

Damage can also extend to products that are left outside for staging while in queue for ocean or air freight loading, or from accumulated condensation within a sea container that drops onto the cargo.

Package handling damage

Package handling, whether caused by a person or an automated handling system, may be damaged by:

- Hard shocks

- Scratches

- Drops

- Falling off a conveyor belt

- Falling off a truck

- An entire container falling into the ocean

Warehouse damage

The environment that a package is stored in can impact package integrity. Environmental factors that could adversely affect packages include:

- Compression from stacking

- Dust and sand

- Unstable shelving units

- Forklift damage, such as punctures or improper pallet stacking

Transit testing simulates supply chain’s rigors

Conceptually, transit testing is designed to proactively mitigate any harm that might occur during transit to any of these packages. Although transit testing is designed to protect each of these packages, the product package (or retail package) is the primary package that the consumer sees.

To reduce damage, map out the journey

The transit journey of each product is unique. One product may have multiple transit journeys. Sometimes an individual product is sold through multiple channels, like retail and e-commerce. Likewise, one product may travel to multiple geographical locations.

For example, a product may be manufactured in Southeast Asia and then be transported by ship to the United States where it will then travel by train to a DC. From the DC, the package may travel by truck to be delivered to a retail store or directly to the customer's doorstep.

1. Define the test objective

Each pre-transit test is customized to the unique journey that your product will take. Based on the conditions your product will undergo during its journey, you should carefully define the test objective. The International Safe Transit Association’s (ISTA’s) guide, Getting Started with Design & Testing,1 explains test objectives, including:

- Screening tests, which are designed to avoid serious product damage during shipment.

- Prediction testing, which is more subtle. These tests require test designers to anticipate sources of minor or intermittent damage.

Organizationally, you should decide who, internally, will determine the test objectives. Once the test objectives have been established, you need to be sure to obtain organizational buy-in from everyone on your internal team who will be impacted by what happens to the product during transit.

2. Create a framework for pre-transit testing

ISTA “is a member-based nonprofit that empowers organizations, and their people, to minimize product damage throughout distribution and optimize resource usage through effective package design.” ISTA provides testing frameworks for various conditions that products may experience during shipment. Their frameworks include:

- Non-simulation integrity tests

- Partial simulation tests

- General simulation tests

- Enhanced simulation tests

- Member performance

- Development tests

- Data depot

Should you test the integrity of an individual package or conduct a pilot test?

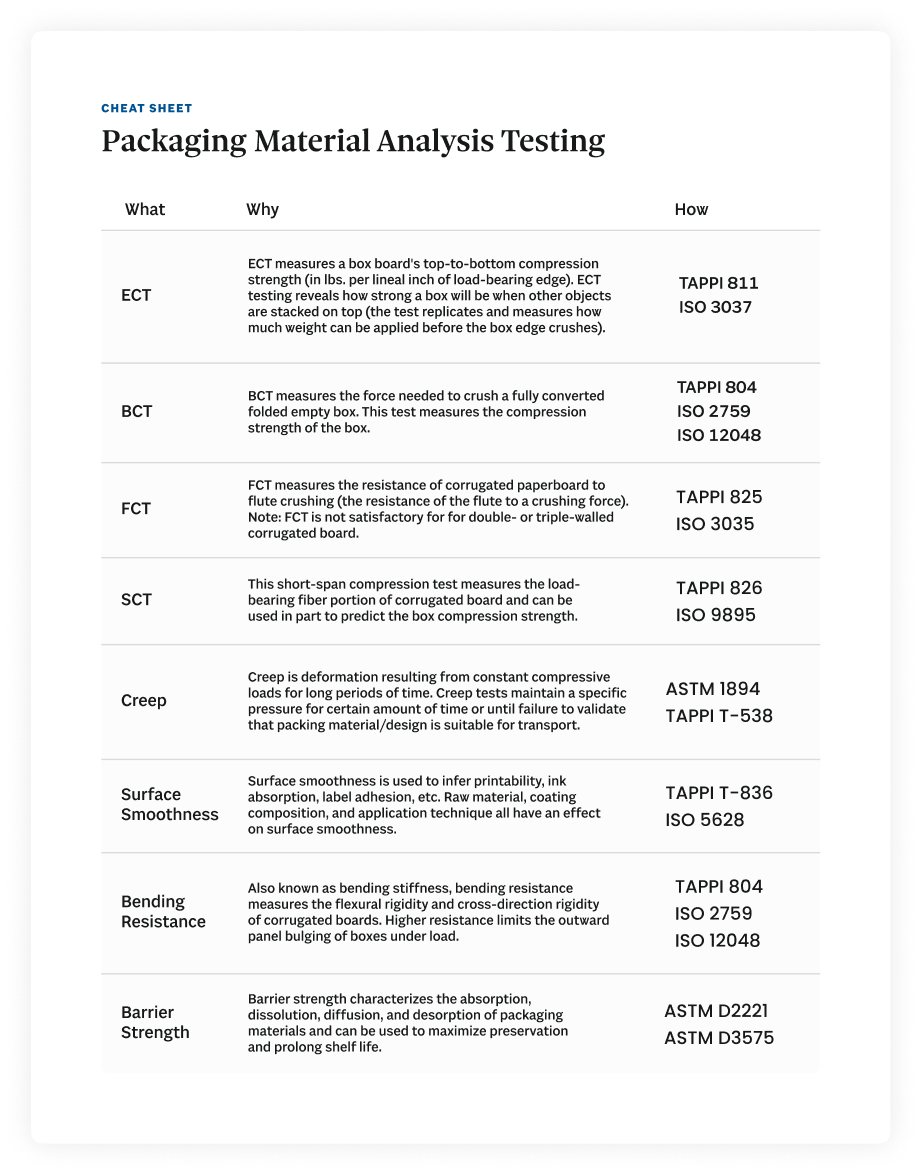

In the laboratory, tests can be conducted to test for specific types of package failures for particular package designs. The chart below summarizes some typical tests:

Should you execute small-scale tests or run a pilot test?

For smaller scale tests, a few packages may be shipped, on an individual basis, to known destinations where an internal team member can perform an inspection on the package and determine whether the package was able to adequately withstand the stress of the journey.

A pilot test includes a more comprehensive simulation of what multiple packages endure during transit. With an increased number of packages shipped, additional data points are available to determine how well the packaging has held up as it travels to multiple destinations.

How do you make sure your test is designed to current industry standards?

Standards organizations frequently update their testing standards. When selecting which tests are appropriate for your pre-transit testing, make sure that you are designing and testing your packaging to meet the most recent set of standards.

If you use a third-party lab to execute a test that you have designed, be sure the lab has up-to-date laboratory certification. It’s a good idea to document your tests so that somebody who is not knowledgeable about the test can understand the test design and execution. If you are testing for ISTA compliance, you should refer to their specific testing documentation requirements.

|

| Our testing lab in Shenzhen is equipped to handle many of the ISTA tests to ensure the packaging we design can withstand the demands of an international supply chain. |

Experienced packaging solutions providers can provide testing services to monitor retail packages in cartons to document force to the product during drop impacts or vibration testing. These providers can generate reports to support validation tests.

You should also determine whether you have internal and external reporting structures that require proof that you have done pre-transit testing. If so, do you have resources available that can accurately meet the documentation requirements?

Expertise enables a more successful testing process

Designing a testing framework that precisely matches your product’s journey is a process that requires experience. Some transit routes may require a more nuanced understanding to accurately anticipate what conditions a product may encounter during transit.

The impact of rain on air cargo is a potential packaging challenge during transit. For example, an apparel manufacturing company that was expediting shipments via air freight experienced product damage when their product sat on the tarmac during adverse weather conditions. The packages became saturated during a downpour. As the packaging was not designed to be water resistant, the packaging failed to protect the apparel from the rain. Consequently, the product was significantly damaged.

3. Define acceptable tolerances for product damage and packaging degradation

In an ideal world, each and every product would arrive at its destination intact with no damage to the packaging. Pragmatically, this can be a difficult and expensive goal to achieve. Your organization should define how much damage it is willing to tolerate both to the product and to the package. Packaging World categorizes this concept as Product Damage Tolerance (PDT) and Package Degradation Allowance (PDA).2

Product Damage Tolerance (PDT) refers to defining how much damage you might be willing to accept on your delivered product. For example, you may define that the product needs to arrive fully functional, but small aesthetic damages, like tiny scratches on the bottom of a product may be allowed. Typically, “tiny” would be defined with specific length and width dimensions to clarify the acceptable size of a scratch.

Package Degradation Allowance (PDA) definitions may include whether small punctures to the outside shipping carton are allowed and whether the carton sealing method needs to remain completely intact.

An additional consideration is that packaging has a shelf life. Packaging is designed and tested based on how long the product will be stored either in a warehouse or on a store shelf. Package design should also include the shipping and handling criteria that is needed to protect the product and ensure that packaging degradation is avoided.

Each brand needs to determine product damage tolerances for their products. If product damage occurs during testing, damage can be discussed after testing is concluded. In some instances, minor damage may be acceptable. Significant damage would require packaging redesign.

4. Design packaging for the harshest conditions the product will endure during shipment

One product, defined as an individual SKU, may be sold through different channels. For example, a blue standard sized flashlight may be sold through e-commerce or through brick and mortar retail. This blue flashlight may be manufactured in Asia and distributed globally.

Ambient temperature conditions on vessels, container trucks, DCs, warehouses, and the last mile of delivery vehicles will vary based on weather conditions in various geographies. In certain parts of the world, the package may be subjected to a harsher transit journey than in other parts of the world. Variability in the harshness of a journey may be caused by environmental, economic, workforce sophistication (including training levels), or any other assortment of factors.

To simplify order fulfillment requirements, manufacturers are motivated to package each individual SKU identically. When each product is interchangeable with each other, order fulfillment is simplified. Whether the blue flashlight will be sent to hot, sandy Arizona or cold, snowy Alaska, the packaging of the blue flashlight will be identical.

In some instances, this may cause a product shipped via the least harsh supply chain to appear “overpackaged” when, in reality, the packaging was designed to withstand the rigors of the harshest supply chain the product travels through. Creating a singular package design that is suitable for disparate retail environments and differing transit routes can be quite challenging. Explore insights into overpackaging in this related piece, How Much Air Do You Transport?

To box it up

Brands typically aim to give customers a pleasant and gratifying experience when they receive a new product. Properly designed packaging, that can withstand transit stresses and arrive, unblemished, at the customer destination is the goal of packaging designers. When pristine packages arrive at a customer location, brand integrity is preserved and expensive returns are prevented. Proper transit testing is all part of running an optimized packaging program.

How transit testing saves you from high returns and damage rates

- Measures packaging’s ability to withstand major sources of damage, including crushing, bending, deformation and more.

- Anticipates potential sources of minor or intermittent damage.

- Simulates expected conditions of a package’s journey through the supply chain.

- Ensures your packaging design adheres to the latest industry standards.

Sources:

- Getting Started with Design & Testing, ISTA

- Five Considerations for Preventing Product Damage Prior to Launch, Packaging World